Facts in Movies: A Study in (repeatedly) Missing the Point

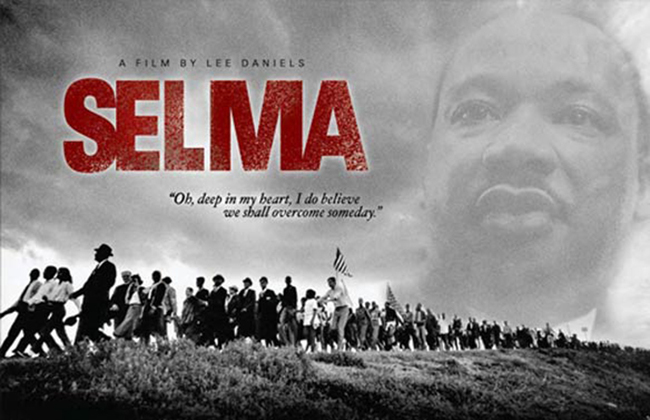

The recent Slate review of Selma, a new film on the Civil Rights movement (and in particular the landmark Selma to Montgomery marches), attacks those critics who dare mention the movie’s occasional historical inaccuracies. It claims that these persons (none of them cinema reviewers, it should be noted) are collectively missing the point, on the grounds that Selma “isn’t a documentary or even dramatized history” – “it is a film based on historical accounts, and like all films of its genre, it has a loose relationship to actual history”. A valid argument, surely, but one that merits closer attention.

Apparently the movie doesn’t really do justice to president Johnson, though to be honest I’m not sure he ever did either.

It is obvious, for one, that a work doesn’t have to be anchored in reality to be considered art. Realism, after all, is only one part of cinema, as it is of say, the fields of literature or fine art (thankfully there’s no such thing in music, I dread to think what that would be like). Nonetheless, this position doesn’t quite work in the same way when confronted with movies that profess factual basis, the problem being that these are partly created to broaden our understanding of actual events. Far from being just a drama, Selma is made for history, by history and (thus) answerable as history – note the questionable use of Lincolnian rhetoric: yes, it is ironic. Still, when a film asserts its historical foundation, it becomes its necessity (and indeed its responsibility) not to change that foundation, especially under the constraints of “artistic license” – a nebulous expression these days synonymous with drama (see Argo). To do the contrary is simply disingenuous. Moreover, any movie that prides itself on its historical nature should not frown at criticism on that very nature, and accept it as an integral part of its appraisal.

Before continuing, and in case any of you thought this was all about LBJ, I should mention that I myself endorse the Gore Vidal view that the late president “far surpassed Nixon when it came to mendacity and corruption”. A considerable feat, granted, but no reason to modify his role in the Civil Rights movement.

Upon reading the article (it is admittedly 11 days old, but I am in this as in many other things quite late), I was reminded of the original post-Caravaggio hipster-murderer Thomas Wainewright’s thoughts on the matter. According to Oscar Wilde, the man subscribed to the notion that in art “whatever is worth doing at all is worth doing well”, so that “once we allow the intrusion of anachronisms, it becomes difficult to say where the line is to be drawn”. This is indeed true, and especially so for a political movie, where any fact toyed with can shine a favorable or unfavorable light on any brand of thought. So where must the line be drawn? Well, in movies claiming realism that line must be drawn to facts, obviously.

To illustrate my point, let us look at two very different, and in my view quite telling, examples: Interstellar and Zero Dark Thirty. You’ll be surprised which fares worse.

The former, while widely hyped to be the defining work in sci-fi scientific accuracy, turned out to be far less than that (although far more in many other aspects). For any of you who know about or have studied – as I have, though not as successfully as I’d thought – the joyous fields of astrophysics and astronomy, the lingering feeling received for an Interstellar session was clearly one of anger. It seemed as if I, along with all audience members, had effectively been duped, an inordinate amount of the movie’s science verging on the nonsensical. That feeling must have been the very same affecting those Civil Rights (or LBJ) historians who watched Selma, and saw that the movie had taken them, if very slightly, for fools. Of course, the respective artistic values of both these works encompass much more than their accuracy in these matters. It should nonetheless be taken into account.

Which is what brings us to Zero Dark Thirty. The difference with this film is that the truth of its factual foundation is still very much opaque. Namely, the point of contention – that torture led to the information necessary for Bin Laden’s elimination – isn’t as clear as some would like it to be. For those of you who watched it, remember that it isn’t the actual torture which leads to information, but a stark relaxation of it (in the form of a nice breakfast) which makes the convict spill the beans, as it were. I haven’t read the CIA Torture Report’s full 500 pages (terribly sorry), but I have doubts as to whether the torture-never-yielded-information conclusion takes this into account. All this is, of course, assuming the movie is as based in fact as it claims to be, something which we will most likely be unable to verify until declassification hops along… a few decades from now.