Syriza and the Perils of Populism

You would think that, given the track record (if not its actual tenets), populism would by now enjoy the same kind of reputation usually reserved for such antiquated nonsense as, say, Czarism. If ever interested in political thought, one only need go as far as Plato (assuming a start at the beginning) to find an attack on the practice, and the obvious realization that an appeal on individual desires and passions does not exactly make the best political platform (and in practice deviates rather heavily from it). Although Plato was conveniently writing about the ancient, non-Syriza, version of Athenian democracy, history is riddled with examples quite as good, if not better – the best known involving an Austrian painter, vague German shouts, and distinctly American facial hair.

I am of course being a bit harsh on the matter, since nearly all politicians take part in some form of populist discourse – the bulk of indulgences occurring during their campaign season. It is in fact a staple of the job, and unlikely to go away as long as a country’s average voter has little real idea of what’s at stake (a common problem that finds its roots in education… but I digress).

“Any public man has every right to try and trick us, not only for his own good but, if he is honorable, for ours as well.” As ever reliable with the turn of phrase, Gore Vidal does hint that the complications are found elsewhere, and he’s right. The real difficulties come when the power-hungry decide to turn their silly, appealing words into actual policy. Whether due to raw cynicism or actual (dangerous) belief, this course of action often has trouble avoiding an outcome verging on the catastrophic. A good recent example would be Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez, whose policies left the country’s economy on the brink of collapse; closer to home, we find historic Detroit mayor Coleman Young is regularly used in political classrooms as illustration to the fact.

So then, how can one know whether or not his favored politician is a spineless populist, or just shamelessly using the rhetoric as election fodder? Well, it may be tough to tell, but usually the best indication is still figuring out how much outward idiocy has sipped through to his political plans. If you think religion dominates your leader’s policies, you may well be on your way towards autocracy (see Turkey) and other nastiness. Similarly, blaming foreign powers for (all) your problems, “directing domestic discontent outward”, will lead to the same results, my sweet Hungarians.

Thus we arrive, almost by necessity, at Syriza, who, with a petite far-right party, currently forms Greece’s new power couple. At birth, and presumably still so now, a left-wing amalgamation of more moderate socialists with radical anti-capitalists, Syriza recently won the latest Greek parliament snap election, only short a few seats of absolute majority. Needing, as a result, to partner with another smaller elected faction in order to form a governing coalition, they allied with their country’s very own nationalist and right-wing group, the Independent Greeks. If that may seem surprising to some (or even treacherous, to a few), it further showcases what should by now be obvious to all, that radical and conservative extremists are in essence very close. In this case, what unites the two parties is an apparent rejection of the harsh austerity measures imposed upon them as conditions for the country’s bailout. Though this stand against the EU is in many ways honorable, the coalition’s policies may absolutely not be.

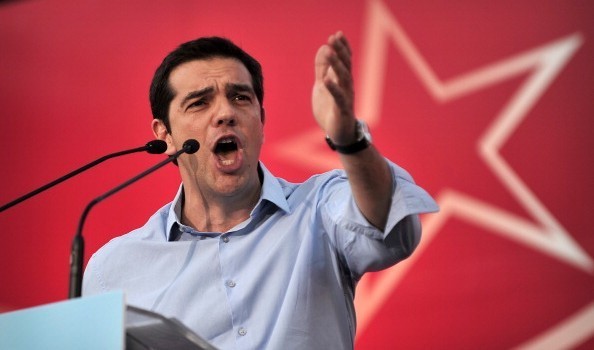

Alexis Tsipras, Syriza’s very own angry young man.

While the austerity measures are, it’s true, partly to blame for the current tortured state of Greece’s economy, they are quite far from the biggest cause – and are in fact ill-designed attempts at salvaging it. To put it simply (and so without the nuance or depth required to avoid a careful frown from forming on the face of the budding scholar), the Hellenic debt crisis was caused by its successive governments and economic actors’ common delusion that the country was operating at a level of wealth roughly comparable to that of Western Europe. Some governments lied to borrow at low interest rates from a very gullible (or cynical) EU, while private banks joyfully offered generous loans to private individuals, believing (or not, depending as always on your tendency to see cynicism) on the relative richness of the good Greeks. The problem was, of course, that the country had absolutely no industry strong enough to support these expenses, and the whole system came crashing down shortly after the vast financial cock-up of 2008.

Considering this sinister background, Syriza campaigned and won on the promise of ending the hated austerity measures, which often accompanied, and sometimes caused, the spectacular fall of Greece’s most important economic indicators (employment, GDP, individual wealth, etc…). Nevertheless, the country still needs EU money – especially considering no reputable private creditors would ever go near it – to support itself, which is why the current negotiations are so important.

On the question of whether or not the coalition could let its populist tendencies permeate into policies, one should for now adopt an attitude of alarmed ambivalence, if possible. Forgetting even the party’s close relationship with Putin’s Russia, who’s ever so fond of a losing EU, as a new manifestation of traditional Christian Orthodox affinities, one has reason for concern. Both right-wing and leftist extremists find meaning in isolationism – and thus extreme state interventionism within the economy. As any student of economics will tell you, nationalist policies are never quite a good thing for a country’s wealth, and in fact tend to impose awful consequences on a vast majority of the population (to the benefit of the few, I should add). This attack on the proposed US-EU free trade deal is thus a perfect example, as anyone with even cursory knowledge of the situation can tell you that most wealth generated by free trade agreements end up going to the common man, mostly because prices are lowered significantly. In addition, and this is where populism shows its lovely face, it should be noted that here the specific point of contention was in fact rather made up by the attacking parties. Delightful.

Syriza was elected, like all populist parties, mainly on promises it cannot keep (an argument can be made that all parties are elected that way, but populism always wins on the sheer scale of its deceptions). Whether it can rise above them and restart the Greek economy one will have to see, but I’m afraid that scenario would be more of a happy surprise than an expected return. I do hope to be proved wrong.