Pnin, or the Trivial Tragical

Christopher Hitchens once said that it took decades for him to gather enough confidence (“dare the attempt”) to write on Nabokov, and one can hardly blame him (the nice little essay he ended up giving us is a worthy read nonetheless). I have (perhaps unfortunately) taken significantly less time, not simply because my opinion of myself verges on the mountainous, but because I am quite sure that with the amount of literature already existing on the man I won’t really be saying anything new. A comforting thought.

“The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness.”

This famous phrase, besides serving the role of glorious opener to Nabokov’s brilliant autobiography Speak, Memory, is a perfectly worded insight into the writer’s mind… one that could’ve only been written by him, in fact. It becomes clear (or at least is should) to all who have read his works that a certain ‘darkness’ is always present; a mark of worthy realism, I should say, as in no novel of his does the passage of time happen without grave injury. What possibly could Lolita, Pale Fire or Transparent Things be without loss and nostalgia? The same is true of today’s petite masterpiece, Pnin, albeit in a slightly different manner.

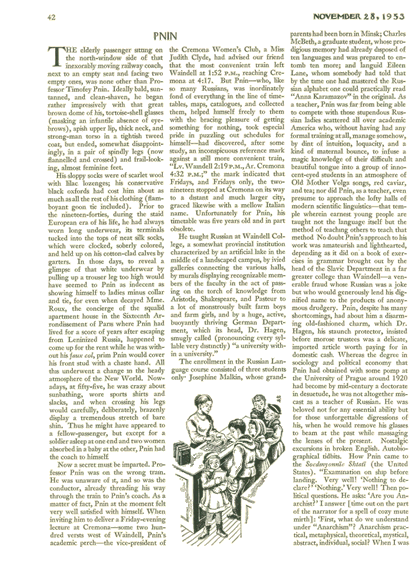

Pnin’s first chapter, found in the New Yorker (1953)

In many ways a collection of short stories, the book centers on an émigré Russian academic, Timofey Pnin, and his escapades about New England and university life. It came out – at least in its present form – in 1957, as an expansion of the pieces published as installments in the New Yorker, while Nabokov toured the country looking for a publisher courageous enough to do sweet Lolita. Through the main character’s foreign mannerisms and its at times outlandish events, the novel is very much comedic; and one cannot help but feel disarmed by the hapless professor’s endearing misunderstandings of the country he now inhabits.

“My name is Timofey, […], second syllable pronounced as ‘muff’, ahksent on last syllable, ‘ey’ as in ‘prey’ but a little more protracted. ‘Timofey Pavlovich Pnin,’ which means ‘Timothy the son of Paul’. The pahtronymic has the ahksent on the first syllable and the rest is slurred – Timofey Pahlch. I have a long time debated with myself – let us wipe these knives and these forks – and have concluded that you must call me Mr. Tim or, even shorter, Tim, as do some of my extremely sympathetic colleagues.”

Nonetheless, to reduce Pnin solely to those things (as some critics have) would be criminal.

Using a process he earlier employed not without genius in Speak, Memory, Nabokov builds every one his vignettes towards a lingering ‘darkness’ and, doing so, emotional depth. In effect, he manages to balance trivial comedy with tragedy, as the eponymous hero is constantly reminded that his current – mostly inconsequential – existence follows in the footsteps of a tragic past. So it is in the first chapter, after finally arriving at a provincial American town, Cremona, to deliver a lecture (following a somewhat farcical voyage), that Pnin is suddenly gripped by memory: “Murdered, forgotten, unrevenged, incorrupt, immortal, many old friends were scattered throughout the dim hall among more recent people”. These dramatic surges end up giving us a picture of Timofey that is remarkable in its completeness, the entirety of his personality and life laid bare with greater complexity than any ‘stranger in a strange land’ normalcy could ever achieve. As is often the case, Nabokov excels in his grasp of detail.

The method’s triumph is found (in this reviewer’s opinion) at the close of the second chapter. After joyfully settling into life as the lessee of two fellow academics, staying in their daughter’s former room, no less, Pnin is visited by his cold, vulgar and cruel ex-wife, who needs money for her son. The chapter ends in the most endearing way – both heartbreaking and humorous – with the wife, Joan (pronounced “John” by the Russian), coming home to find Timofey crying uncontrollably and looking for whisky in the kitchen. Following, first, an attempt at consolation through comic strips he can’t comprehend (“Impossible,” said Pnin, “So small island, moreover with palm, cannot exist in such big sea.”), and second, her husband’s tactful and noiseless slip away the moment he realizes what’s happening, the author decides to end the chapter with a simple yet terribly effective:

*“Doesn’t she want to come back?” asked Joan softly.

Pnin, his head on his arm, started to beat the table with his loosely clenched fist.

“I haf nofing, ” wailed Pnin between loud, damp sniffs, “I had nofing left, nofing, nofing!”*

It is worth noting that the ever present shadows of death, nostalgia and broken hearts manifest themselves physically every time. These reminders arrive with tears in the second, third and sixth chapters, heart palpitations in the first and fifth, and back-pain in the fourth… Again an example of Nabokov’s brilliance; an understanding of human emotions beyond that of the majority of other writers (or artists for that matter, but that’s another story). That sinking feeling often attacking Pnin where nostalgia strikes, is a testament to the author’s playful artistic emphasis of what he deems truly important. Unlike say, Joyce, whose emotions are buried under mountains of breathtaking prose (i.e. the two don’t work together but side by side), Nabokov tactfully shines a light on what matters (the emotional depth, key to our understanding of Pnin the man), and brings it out from amid his own purple complexity.

Thus, the tragi-comedy is served with equally compelling servings of either side, by emphasizing Timofey’s unfortunate eccentricities and limitations on one, and his past on the other. The result, bittersweet as it is, manages to capture life more fully than (almost) any work, definitely as well as his masterpiece autobiography, and in near-infinitely less pages than the many other famous attempts.